36 What can the pandemic ask the classroom

36.1 This nameless time during a pandemic

In March 2020, the onset of the novel coronavirus pandemic in Brazil and the necessary public health measures for social isolation to prevent contagion led to an immediate shift in daily life. This was notably evident in the uncertainty about the future and the fear of death, with political and social effects both at home and at work. As days passed in this new pandemic world, different levels of response to Covid-19 became clear. Factors related to class, territory, and income impacted social isolation and, consequently, the alarming death tolls. According to Cerqueira (2017), Brazil faced an unprecedented public health crisis, revealing multiple pandemics within a pandemic, such as the increase in lethal violence and the deepening of social inequalities.

This text reflects the experience of living through this historical time as individuals engaged in a graduate program at a public university, specifically a Professional Master’s program in Psychology and Public Policies in the interior of northeastern Brazil. It dares to think about the present, weaving ethical and political effects of the pandemic for the field of education, specifically in the face of the challenge of a remote and virtual classroom.

During a teaching internship course in 2020, an audiovisual device titled “What Can the Pandemic Ask the Classroom?” was developed. It involved dialogues and exchanges between individuals from various territories engaged in education, art, and human rights policies in the state of Ceará. Through this, we wove meanings about training, experience, and learning in a pandemic world.

Conversation is a necessary sign for the development of this device, as isolation and excessive exposure to virtual screens produced social distancing and reduced spaces for dialogue and affective exchanges, even though we were continuously connected through screens, live streams, and remote classrooms. Therefore, we emphasize that this text expresses a polyphony of voices, mixing chronological times of the pandemic world. These connections range from the teaching internship course, with participation from the master’s student Thamila Santos, under the supervision of Professor Dr. Érica Atem Gonçalves de Araújo Costa, where the audiovisual device “What Can the Pandemic Ask the Classroom?” was created, to the present moment in 2021, in dialogue with master’s student Milena Assunção, a student from the second cohort of the master’s program, and an educational advisor in the municipality of Sobral. Her research project raises questions about thinking of education beyond institutions, productivity, and the successful numbers of Sobral’s education system.

Thus, our voices will meet during this writing, at different times, but under the perspective of a common plan to think about education and public policies, with the desire to continue building spaces for conversations; to enable meetings between the participants of the device “What Can the Pandemic Ask the Classroom?” and, later on, the more than 416 people who viewed the videos on social media. These videos became discussion topics in the Psychology classroom at Luciano Feijão College, in teacher training sessions at the Permanent Training School for Teaching and Educational Management (ESFAPEGE), and in training sessions with youth articulators from the Violence Prevention Projects Management Unit. It is, therefore, a gathering of many voices, attempting to understand this nameless time amid a pandemic.

36.2 School, creation, and training

I walk around the world paying attention

To colors I don’t know the names of

- Adriana Calcanhotto, Esquadros, 1992

The world we know can be understood as an invention that becomes real in the act of creation. Inspired by the lyrics of Adriana Calcanhotto’s song in the epigraph, we see that attention is a muscle that can be exercised, as we walk around the world with fluctuating attention, sometimes focusing on one object, sometimes on another. For a sense of comfort and security, we take some elements, or almost all of them, of this created world as facts, as if these compositions had always existed. It is a paradox: we understand that something is an invention, yet, at the same time, it seems to have always existed—and therefore will always exist—as if there were a permanence with tones of essence.

In this sense, following this line of thought, we wish to problematize the school institution. This is because the school is a created place, marked by processes of subjectivation, by forces from temporal textures, which ultimately respond (or attempt to) to socio-historical anxieties. According to Masschelein and Simons (2019), the school “is a historical invention of the Greek polis and was an absolute attack on the privileges of the elites of an archaic order” (p. 105). Thus, the school, in the context of its initial fiction, positioned itself as resistance, a dialogical and democratic space.

The modern school institution, however, dates back to the 18th and 19th centuries. It is configured as an “attempt to dissipate renewal, radical potential” (Masschelein & Simons, 2019, p. 106), meaning this modern model diverges significantly from its Greek origins. Over time, through one of the lines that problematizes this space, the school has been described as a “normalizing, colonizing, and alienating machinery” (Masschelein & Simons, 2021, p. 19). In the Greek polis, the school was a space of confrontation, resistance, and dialogue. Conversely, the modern composition became a well-structured space, with its pedagogical steps and existences well defined. This movement points to an ideal of a rational, disciplined, hardworking subject that maintains the desired flow.

However, the same authors remind us that even if this space seems like a well-centered and captured machinery, there is an unstable, provisional process in this organization. The school is always creating, always in a state of becoming, open and in process.

The question here is how this space is neither fixed nor stable. It is, above all, creation. The fact that the Greek origin was different from the modern one only reinforces the clue that educational practices and inventions are mutable (Brandão, 2007).

Taking these historical nuances as a clue, we can understand that the school does not remain the same over time. It transforms, is contested, responds to socio-historical anxieties, and ultimately recreates itself. Understanding the school merely as a physical space that transmits a certain knowledge would be naive or even a way of denying how political this space is. The school is not and has never been a space apart from society. It is a place traversed by various debates, disputes, and perspectives that see different worlds. We thus have divergent desires for the same object.

Affirming this social and political space of disputes implies understanding that it is not limited to a physical composition since the school is much more than walls and fences. Discussing the school institution inevitably means problematizing the education produced in this space and, more specifically, the subjects produced with the education developed there. According to Freire (1967), “there is no education outside human societies” (p. 35), meaning education, a human creation, can be understood as a set of practices that, while sharing a type of knowledge, also produce, subjectivize, and create a type of subject.

Thus, education is not configured as a practice detached from the world, an ahistorical action; on the contrary, “there can be no neutral, uncommitted, apolitical educational practice” (Freire, 2001, p. 21). From the first word, we affirm how what we produce crosses and forms us. Thus, educating is intervening, creating, and experiencing possibilities.

There is also another important notion: the school is not merely a place for knowledge transmission, where one teaches, and the other learns. We understand and advocate that education always occurs in relation. Affirming this, however, does not deny that there is an expected type of subject in education. Therefore, two aspects of education must be perceived: in educating, there is a relationship between the subjects involved in educational practices; and, being involved in these practices, there are processes of subjectivation, that is, the production of ways of existing.

36.3 The “reinvention” of the classroom: imperatives and urgencies

Door, rows of chairs, board, markers. These are recurring elements in classrooms. They are so common that they can be understood as essential for conducting a class. However, this idea was suspended at the beginning and throughout much of the Covid-19 pandemic. As it was no longer safe to be physically present, the physical classroom ceased to be a routine reality and became a target of precautions and recommendations.

In a matter of days, words like educational technologies, Google Classroom, video classes, WhatsApp, YouTube, and live streams were present in conversations, speeches, and training sessions. It was evident that creating a new way of teaching, experiencing the classroom, was more than necessary; it was urgent and demanded. These demands resonated in an array of tips, tutorials, information, and creative ways to make the “classroom floor” happen despite the physical absence. However, amid such effervescence, there was a pandemic.

A pandemic that, in addition to all public health aspects, brought the worsening and intensification of social inequalities and vulnerabilities. Regarding the school institution, concerns such as food insecurity, violence, and child malnutrition became fundamental points in pedagogical-administrative discussions. Thus, alongside demands and incentives for pedagogical renewal, there were not only logistical questions about what to do with students who are outside this “connected education,” but also another pressing issue: how to think about online classes, hybrid teaching, technologies, if the target individuals of these actions do not have the minimum conditions for survival?

It is not that these concerns did not reach the school, the classroom. But their place was minimal, on the margins of actions. Then came a pandemic that touches various sectors and exposes inequalities, proving that the critical moment might be the same, but the ways of coping and impacts were very different. Inequalities were unmasked in a way that the place of major evaluations lost its prominence, its ultimate goal. How to think about exams, funding allocations, successful actions when the most significant outcry from the disadvantaged population touches basic needs? Hunger, death, extermination, performance. What is a grade compared to a hungry, homeless, unprotected child?

We must also not forget the teachers. Numerous calls arrived for the teaching profession, for example, openness to the new, resilience, creative classes. But did this come or just intensify? This new discourse, cloaked in beautiful, motivational words, reflects a deeper issue, touching on overload, devaluation, excessive demands, and the suffering resulting from the labor. Thus, to some extent, what happened was a kind of removal of a veil covering something that had long resonated.

Amid the entire educational context, which is also social, the question arises: “What can the pandemic ask the classroom?” A broad question that touches not only the pedagogical but also the social, because all pedagogical action is social. But before that, we need to share how this is a question aiming at resonance, effects, and potentials, not merely framing culprits or even confronting practices, some more successful than others. We ask because we know and defend the understanding that problematizing moves, creates, and recreates effects. It is, therefore, to movement that this question relates.

36.4 “What can the pandemic ask the classroom?” as a device for encounter

If the pandemic world produced for us, students and teachers, a physical classroom in a state of interruption, as we walked through this new world with our masks, crowded hospitals, acute shortness of breath, and daily deaths, other sensitivities and affections had to enter the space we shared together with the classroom’s meaning. We bet that experiencing this formative space from the field of sensitivity is to propose paths where one can see, hear, think, and feel the world as a political, ethical, and aesthetic experience.

Therefore, the idea of creating an artistic-political device of fictional encounter without screens with educators, students, and artists in the middle of a pandemic emerged. What to say about this experience that silences us? We were interested in listening to some trajectories crossed by the classroom in the contingencies of a global pandemic, but we knew the demands, the precariousness of work, the fallen bodies, the productivity.

The notion of the artistic-political device has been elaborated in dialogue with the studies of Rolnik (2009, 2019), which operates in the territory of art and politics, from the relationships with processes of subjectivation, culture, and creation. According to the author, the device has the capacity to “create the conditions for such practices to activate sensitive experiences in the present, necessarily different from those originally lived, but with equal critical density” (Rolnik, 2019, p. 97).

From a trajectory of research interests crossed by politics and art, the possibility of doing something where these relationships could appear in the professional master’s program accompanied us. Thus, the possible path we found to respond to the provocations of the teaching internship course was to produce a device of encounter and listening from the field of sensitivity that would provoke voice, body, and narration of agents connected to education during the pandemic.

Thus, we present the experience of encountering eight educators from various fields of training, woven from the question: what can the pandemic ask the classroom? The choice of the eight participants was due to the affective and professional proximity with the researcher-student of the teaching internship course in 2020, Thamila Santos. The people invited to the conversation have intersections with public policies of education and human rights in Sobral. They are teachers from the municipal and private networks, artists, cultural producers, and researchers working in Sobral and Fortaleza. They are Jander Alcântara (theater artist and basic education arts teacher in Sobral), Clara Di Lernia (manager of permanent education at the Violence Prevention Projects Management Unit - UGP-PV, linked to the Human Rights Secretariat), Gisela Nóbrega (Fundamental I teacher at a private school in Sobral), Daiana Maciel (artist and psychologist at the Women’s Reference Center in Maranguape), Neirton Filho (musician, poet, and art educator), Dim Albuquerque (communicator and youth articulator at UGP-PV), Rômulo Silva (PhD student in sociology at UECE), and Léo Silva (peripheral photo-documentarian and cultural producer).

The diversity of voices and trajectories in the field of education interested us for building the device. The different existential territories regarding the classroom are necessary to problematize the political and ethical intersections that weave the formative space. Thus, we invited the participants to respond by audio to a question that would activate memories about training.

We bet on a hybrid format between audio and image languages, as audio invites listening to the subjects through the sound of their voices and the narration of their stories. Moreover, during the most critical period of social isolation, images were exhaustively used during video calls and live streams, which prompted us to think of another format of encounter.

From listening to the responses made to the question “What can the pandemic ask the classroom?”, excerpts from the speeches were selected, and a fictional exchange of dialogues between the participants was created. All audios were listened to by the researcher, and, using a technique of cutting and selecting, commonly used in audiovisual media, elements that aroused problematization regarding the themes of training, memories, affections with the city, work, and the pandemic were selected.

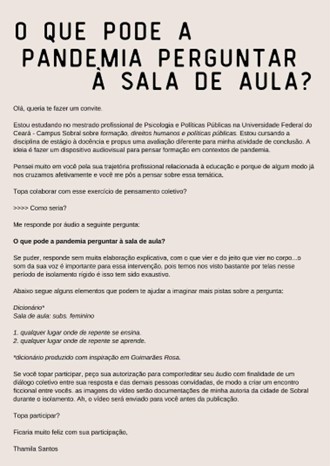

Considering the possibility of not restricting the question to an explanatory or evaluative response, we wrote an invitation letter to inspire the participants to narrate other forms of processuality with their classrooms. We were interested in opening meanings for an experience of affections and the body. Thus, we found it appropriate to share the document as it was sent to the participants since the ways of doing interest us for the methodological and political texture of the paths taken, especially for the capacity to inspire and derive other practices from each reality.

In the invitation letter, we described clues about the experimentation, aligned the objective of the intervention, and explained why we chose not to gather them in a virtual room for this collective dialogue. All in-person activities were suspended, and meetings, classes, work meetings, and leisure moments were mediated by exposure to virtual screens. This was part of our pandemic daily life, so the proposal of a fictional encounter through audios seemed more potent to open other channels of affection and problematization.

Understanding fiction is not about the absence of truth but about creating possibilities for the invention of other realities, as poet Manoel de Barros brings to light when he says, “Everything I don’t invent is false.” Invention is not the absence of truth; it is, above all, the weaving of a path. Fiction, therefore, is an invention of worlds. It is a method for forging proximity between people from such different territories, living different pandemics, through the encounter with a common plan, with the experience of the classroom, through words, pauses, breaths, and sounds.

Thus, the idea was to create an invented dialogue that did not occur in person among the subjects, but which, through the intervention-composition of the researcher, produced a fictional encounter around the same question. The format was previously agreed upon with the participants, who authorized the editing of the audios to form a network of dialogues with everyone’s implications. Their responses served as inspiration for the editing and stitching of a polyphonic, diverse, ethical, and propositional conversation about training policies in pandemic contexts.

The conception of this artistic-political device draws inspiration from cartography, in the studies of authors who intersect between the field of subjectivation politics and art, such as Rolnik (2016) and Kastrup (2004), who forge dialogues with the field of sensitivity as a research method.

With cartography, we perceive and create worlds and research from the idea of composition. As Kastrup and Passos (2016) write, composition is on the plane of forces and affections, it refers to a politics, an ethos, and a commitment to creating a common and heterogeneous world. In the idea of composition, we experience a co-engenderment between researcher and field, which calls the trajectories and limits of the researcher.

In this sense, the encounters among the participants were arranged as a composition. In the sound editing studio, the researcher drew lines between the responses, producing new material from that encounter of voices. This culminated in the final version of an audiovisual material, engendered with video images produced by the researcher of the city of Sobral during the pandemic, creating a way to compose with the images other visualities of the city and the pandemic time.

Thus, this conversation was invented to bring educators together in a time of deep desertification like the pandemic, an experience of not promptly answering questions but lingering in them, observing which cracks or beams of light emerge from their fissures.

36.5 A Way to conclude or an affirmation in desert times

Building a shared path, bringing a polyphony of voices to think about the classroom, speaks of a practice that concerns the historical and relational aspects that traverse this space; of perceiving that the school is an invented creation that constantly recreates itself, that the classroom is not immutable, fixed. On the contrary, we share that this space was one way, and during the beginning of the pandemic, it had to be another, and this will continue to happen, as we do not have given facts but phenomena created and constructed collectively.

The affirmative question highlighted by sharing the device “What Can the Pandemic Ask the Classroom?” is that we can produce an exercise of invention in the field of art, politics, and education that serves as a vital alternative to the desertification of pandemic times and the brutalization of education. The challenge seems to be creating something with people, using art to do it with them, with fragments of conversations, sounds, with images that can be evoked.

The ethical horizon of this material is the possibility of conversations with more people, as already happened in some spaces, such as the dissemination of the videos on social media, screening and discussion of the video with the youth articulators group of the Violence Prevention Projects Management Unit (UGP-PV), in a teacher training class at the Permanent Training School for Teaching and Educational Management of Sobral, and with a psychology class at Luciano Feijão College (FLF).

In this perspective, we highlight some effects already produced through the circulation of this tool in the world, such as an approach with training groups in the municipality of Sobral, whose exchange produced discussions to think about education and training in pandemic contexts. We also highlight an approach with the youth articulators group working in vulnerable territories in Sobral. The videos were shown during the workers’ permanent education processes and enabled discussions about a non-institutionalized school and the impacts of learning in the pandemic in situations of social inequalities.

In this sense, we hope it continues to be used, adapted, made available, and continues to produce effects of problematization and encounter. We hope it serves as a material that is not only a reference for the field of art but also for the field of education, especially because it is a technical product easily replicable due to its virtual accessibility and audiovisual format.

We are interested, in the artistic-political field, in the defense of art as politics, as an announcement of a sensitive sphere in the micro-policies of education. Therefore, this artistic-political device has a character that not only figures in the field of macro-politics but also in the field of micro-politics, aiming to catalyze conversations with and among education agents to produce horizons for classrooms that are more sonorous, narrative, and grounded in the invention of possible worlds.