26 The interface between Psychology and Health: challenges for professional training

26.1 Introduction

With the implementation of the Unified Health System (SUS) in 1990, a nationwide and public system was initiated, based on principles and guidelines common to the entire Brazilian territory, as stipulated in its Organic Law (Laws No. 8,080/90 and No. 8,142/90). This system is oriented not only towards SUS assistance and management but also towards training for the health field. This aspect is seldom discussed, especially in the realm of Psychology. However, to respond to the numerous changes in services and health care and management practices brought about by SUS, significant changes in the training process and the development of professionals to work in this area were and still are necessary (Cavalheiro & Guimarães, 2011).

Since 1986, when the First National Conference on Human Resources in Health was held, the training of professionals for SUS has been among the discussed topics, revealing the need to create programs aimed at this aspect (Silva & Santana, 2015). To systematize and implement a specific policy for the issue of human resources aimed at SUS, the Ministry of Health established the Department of Health Management and Education (DEGES) within the Secretariat of Labor and Education Management in Health (SGTES). This department proposed the creation of a national policy for the training and development of health professionals. Programs such as continuous education centers, AprenderSUS, VerSUS, the Health Work Education Program (PET-Saúde), and Multiprofessional Residencies were developed for this purpose. However, despite the numerous advances these programs represent for training linked to SUS, their implementation and operation present various challenges, such as:

- overcoming the emphasis on content-based and primarily technical training;

- addressing the deficit discussion on social, ethnic, ethical, and political factors, prioritizing formal and technical aspects of SUS and services;

- addressing the fragmentation of actions at specific levels, distancing from integrative, interprofessional, and intersectoral proposals (Cavalheiro & Guimarães, 2011).

Additionally, as pointed out by Almeida Filho (2013), we cannot ignore that the crisis in SUS is multifaceted, composed of factors linked to underfunding and an emphasis on bureaucratic management, which lacks the capacity to adopt conceptions aimed at practices based on integrality and equity in its actions. Furthermore, there are distortions in the training models of health professions, among which we can list: the construction of closed curricula with little interdisciplinary and interprofessional foundation, promoting an emphasis on specialties in isolation and maintaining the process of alienation of professional segments in this field, making it difficult to carry out work in multi- and interprofessional teams in services.

Thus, the training process for the health field ends up, even during undergraduate studies, constituting a kind of “premature specialization,” marked by few general studies that promote a broad vision of what constitutes the health knowledge field, the health-disease process, and care based on the critical framework of population needs and the social determinants of health (Almeida Filho, 2013). Such statements can be demonstrated by studies highlighting the emphasis given during health training to theoretical and practical content that focuses on segmented aspects of the individual, directed towards biophysiological characteristics, disregarding the need for graduates to understand the health-disease process integrated with the social, historical, and political characteristics of the population (Damiance & al., 2016).

Discussing the realm of educational policies, Carvalho and Ceccim (2009) problematize health graduations, stating that they are not directed towards the theoretical-conceptual and methodological training that promotes the construction of competencies focused on the integrality of their actions in SUS. On the contrary, health training processes still accumulate a content-based tradition, based on an excess of workload and composed of technical disciplines, disconnected from proposals that include articulations with research and extension, predominating an encyclopedic format oriented towards disease, seeking means of intervention for user rehabilitation/cure.

Psychology has emerged as an important profession in the health field, with a significant expansion of its insertion and performance at various levels and services in SUS. However, according to Carvalho, Bosi, and Freire (2009), when challenged to enter the field of Collective Health, Psychology professionals face a complex context, where dynamics and historicity are expressed through the prevailing care model. This model is marked by political issues and professional cultures that cause discrepancies with the principles and parameters that encompass SUS. The authors reiterate that upon entering the health field, psychologists end up resorting to knowledge based on traditional clinical practice, not making the necessary revisions and contextualizations to guide their professional knowledge and practice in SUS.

Dimenstein (2001) supports this debate by pointing out that even though the more massive entry of psychologists into public health institutions has expanded the places of professional performance, this scenario has not promoted significant changes concerning the conceptual-epistemological and methodological foundations that underpin the actions developed in these spaces. Therefore, no significant updates have been made to contextualize these markers to promote reinventions in the traditional conceptual parameters of the profession, which are oriented towards the privatist clinical-hospital realm. Although there have been advances in this regard, as pointed out in more recent studies (Dimenstein & Macedo, 2012), these aspects have not yet become hegemonic in the profession, configuring a new professional reality for psychologists working in SUS.

Based on these problematizations and the need for studies that deepen the epistemological, methodological, and ethical-political foundations of Psychology in SUS, we aim to analyze how Health and, more specifically, the debate around Collective Health have been integrated into Psychology training in Brazil, following the establishment of Resolution No. 8, of May 7, 2004, which institutes the National Curriculum Guidelines (DCN) for undergraduate Psychology courses and affirms it as a health profession (Conselho Nacional de Educação, 2004).

26.2 Method

This is a study with a documentary design, focusing on the analysis of the Pedagogical Projects of Psychology Courses (PPC) in Brazil, documents available in the public domain (Gil, 2002). The data source was the Ministry of Education’s database on Higher Education in Brazil, which indicated, in the 2019 Census, the existence of 929 Psychology courses, 829 of which were in private institutions and 100 in public institutions. Once each course was nominally located, a search for the Pedagogical Projects of Psychology Courses (PPC), available in the public domain, was conducted on the website of each Higher Education Institution (IES).

After locating the respective curricula, a filter was applied to the set of disciplines, syllabi, and bibliographic references to locate curricular components related to Health/Collective Health. The search for such information considered the following descriptors: “collective health”, “health management”, “health planning”, “health education”, “permanent health education”, “epidemiology”, “integrality”, “multidisciplinary”, “multiprofessional”, “interdisciplinary”, “SUS”, “territory”, “care”, “health practices”, “citizenship”, “rights/human rights”, “public policies”, “health policies”, “social policies”, and “mental health”. All information was organized into a database containing the identification of the IES and the located curricular components.

The analysis was aided by the IRAMUTEQ software, which, integrated with the R software through the Python programming language, enables the performance of statistical analyses on textual corpora as well as tables consisting of words. This software allows for different types of textual data analyses, from the simplest, encompassing word frequency calculation, to the most complex, characterized as multivariate analyses (Camargo & Justo, 2013). In this aspect, we opted for the analysis using the Descending Hierarchical Classification (CHD) Method, which classifies text segments based on their respective vocabularies, aiming to construct classes that can present both similar and different vocabulary among themselves. Additionally, all analyses performed in IRAMUTEQ were interpreted in light of the epistemological, methodological, and ethical-political foundations of Collective Health. Finally, for ethical reasons, even though the documents are available in the public domain, we considered the anonymity of the courses in presenting the information.

26.3 Results

The search for the Pedagogical Projects of Psychology Courses available in the public domain on the website of each of the 929 IES returned 64 Course Projects. However, after applying the descriptors related to Health/Collective Health mentioned earlier, 30 curricula were selected, presenting curricular components related to the investigated theme, constituting the research corpus.

To provide a more general characterization of the analyzed material, we organized the Course Projects into the following categories: 12 courses in public IES and 18 in private IES, with 3 located in the North region, 12 in the Northeast, 3 in the Midwest, 6 in the Southeast, and 6 in the South. Regarding the size of the municipality where the courses are located: 10

are in large cities, 2 in medium-large cities, 8 in medium-sized cities, 6 in medium-small cities, and 4 in small cities.

Next, we examined each of the 30 curricula and found at least 727 disciplines, consequently 727 syllabi, as well as 428 bibliographic references related to any of the Collective Health descriptors that guided our search. Subsequently, these components were separately analyzed in specific textual corpora using the Descending Hierarchical Classification (CHD) Method, meeting the minimum criterion of 75% corpus utilization indicated by the literature (Camargo & Justo, 2013).

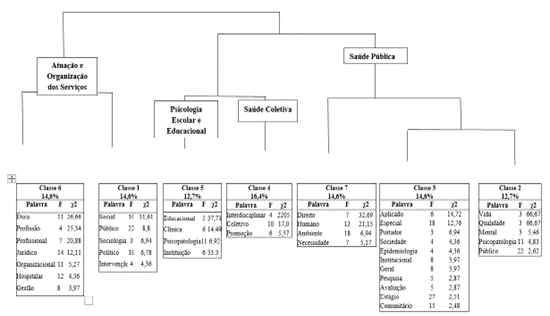

Figure 1 presents the first analysis performed using the names of the identified PPC disciplines. Sequential divisions were made in the corpus until 7 classes were formed. The first division created three subcorpora. The first subcorpus, “Performance and Organization in Services,” consists of classes 6 and 1 and represents the second-largest percentage of text segments from the disciplines (29.2%). The words characterizing this subcorpus were: “ethics,” “profession,” “professional,” “management,” “intervention,” among others. The second subcorpus split into two: “School and Educational Psychology,” encompassing class 5, and “Collective Health,” comprising class 4. Class 5, “School and Educational Psychology,” corresponds to 16.4% of the text segments, consisting of words such as “educational,” “clinic,” “psychopathology,” and “institution.” Class 4, “Collective Health,” represents 16.4% of the text segments, characterized by words such as “interdisciplinary,” “collective,” and “promotion.” The third subcorpus, “Public Health,” includes classes 2, 3, and 7. Combined, these classes represent the largest percentage of text segments from the disciplines (41.9%). The words representing this subcorpus were: “right,” “environment,” “applied,” “evaluation,” “public,” among others.

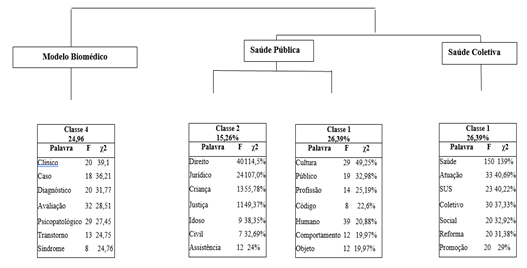

Regarding the analysis of the syllabi, the result is depicted in Figure 2, where sequential divisions were made in the corpus until 4 classes were formed. The first division created two subcorpora. The first subcorpus gave rise to class 4 – “Biomedical Model” – while the second subdivided into three, forming classes 1 and 2 – “Public Health” – and 3 – “Collective Health.”

Classes 2 and 1, “Public Health,” correspond to 15.26% and 26.39% of the text segments, respectively. These are the most significant classes compared to the others, consisting of words related to the Public Health field: “right,” “public,” “behavior,” “legal,” “civil,” “assistance,” among others. Class 3, “Collective Health,” represents 33.3% of the text segments. This class refers to content encompassing the field of Collective Health and SUS, comprising words such as “health,” “care,” “SUS,” “collective,” “social,” “reform,” among others. Class 4, “Biomedical Model,” represents 24.6% of the text segments, referencing content from psychopathology and diagnostic psychiatric manuals, consisting of words such as “clinical,” “case,” “diagnosis,” “evaluation,” “psychopathological,” “disorder,” among others.

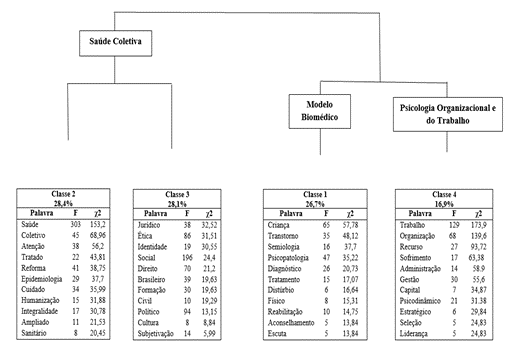

Regarding the analysis of references, the result is presented in Figure 3. Sequential divisions in the corpus of references resulted in 4 classes. The first division generated two subcorpora. The first split into classes 2 and 3; the second included classes 1 and 4.

Classes 2 and 3, “Collective Health,” represent 28.4% and 28.1% of the text segments, respectively, and together account for the largest percentage (56.5%). These classes consist of elements related to the Psychiatric Reform movement and the Collective Health field, highlighting words such as “health,” “collective,” “care,” “reform,” “culture,” “subjectivation,” among others.

Class 1, “Biomedical Model,” corresponds to 26.7% of the text segments, consisting of words such as “disorder,” “semiology,” “psychopathology,” “diagnosis,” “disturbance,” “treatment,” among others. Class 4, “Organizational and Work Psychology,” represents 16.9% of the segments, comprising terms such as “work,” “organization,” “resource,” “administration,” “management,” “capital,” among others.

After organizing the results by analyzed curricular component (discipline names, syllabi, and references), we present the categories that guided the data discussion:

- Biomedical Model;

- Public Health Model; and

- Collective Health Model. These were oriented by the following analytical axes:

- health conceptions,

- practices, and

- ethical-political guidelines.

26.4 Discussion

26.4.1 Biomedical Model

The analytical category we termed the “Biomedical Model” was related to words referring to the Psychiatric and Psychopathological field: “psychopathological,” “disorder,” “syndrome,” “diagnosis,” “disturbance,” among others. Of the total syllabi (n = 727) and bibliographic references (n = 428) in the 30 analyzed curricula, at least 24.96% (n = 181) of the syllabi and 26.7% of the reference titles (n = 113) were related to the “Biomedical Model.”

In terms of health conceptions guiding the training process in Psychology based on the Biomedical Model, Sobrosa et al. (2014) problematize that this model has its origins dated to the early 20th century, characterized by the understanding of health as the absence of diseases, emphasizing biological aspects accompanied by physiological alterations resulting from biochemical imbalances, lesions, and/or infections:

“Main schools of psychopathology. Diagnosis in psychopathology. Classical psychiatry. Psychoanalysis and current diagnostic manuals, namely ICD 10 and DSM V. Meaning and evolution of concepts of normality and pathology” (PPC 13).

Except for the reference to Psychoanalysis and the indication of understanding the differentiation of its clinical structures in a few analyzed syllabi, overall, we observed the absence of more critical discussions about the syllabi gathered here to problematize the hegemonic paradigm in health under the ideal of cure and question the notions of normal and pathological, allowing little (if any) broader understanding of the health-disease-care processes. By emphasizing health training concepts with epistemological bases grounded in this model, Psychology ends up focusing on segmented aspects of the individual, primarily directed towards describing characteristics or psychological phenomena stemming from biophysiological or personality alterations, which will support theoretical-methodological markers centered on clinical-therapeutic approaches (Bernardes & Guareschi, 2010).

In this training model, the definition of health falls into naturalistic views, bringing only a predicted and ideal development of humans. As such, there is no relation to living conditions and society or the SUS principles in which it is immersed. Instead, it locates the causal factors of illness within the individual, promoting a notion that health depends solely on an effort to recover a lost previous state or prevent a future health problem from establishing itself (Camargo Jr, 2013).

Regarding the practices addressed that encompass the biomedical category, these have a curative bias, focusing on symptom remission, primarily directed towards the traditional clinical and hospital realm:

“Initial interview, anamnesis, and feedback. Clinical diagnosis and intervention. Mental examination and the issue of diagnosis. Identification of different symptoms in mental functions and clinical disorders” (PPC 10).

Thus, the relationship between Psychology and Health in the training processes here acquires characteristics close to what Oliveira, Balard, and Cutol (2013) call the “Flexnerian Model.” This model is based on anatomical-physiological aspects, directing actions towards the etiological agent and professional postures, which barely consider social and historical aspects. By approaching this model, Psychology training relies on the same reading keys to understand the psychological phenomenon, focusing on studying personality (in terms of structural and functional structures).

In these terms, Cintra and Bernardo (2017) argue that it is necessary to renew the set of practices presented and discussed during Psychology training, not to deny the said model, but to create a constant process of questioning the biomedical paradigm and foster students’ and teachers’ creativity in developing new intervention strategies. Thus, training would be synonymous with exercising creative autonomy to produce both theoretical and practical singularities, thereby broadening conceptions about the health-disease/suffering-care process.

Regarding the ethical-political guidelines encompassing the biomedical category, these concepts were limited to the professional code of ethics, covering issues of professional confidentiality and the production of reports and opinions:

“Main foundations of the professional code of ethics for psychologists. Structure and administration of the Professional Psychology Council and current legislation. Ethics in professional practice. Professional confidentiality” (PPC 7).

There is a notable emphasis on training in ethical-political aspects limited to professionally normative postures deemed appropriate and consistent with the professional code of ethics in Psychology. This scenario supports Dimenstein’s problematizations (2001), asserting that the dominant perspective of psychologists’ performance in the health field remains distant from social and political commitments in the profession, based on the concrete needs of the territory.

26.4.2 Public Health Model

The analytical category we termed the “Public Health Model” was related to 41.9% (n = 305) of the text segments related to discipline names and syllabi. According to Souza (2014), this model refers to a part of Medicine that proposes to intervene in public administration to keep the population healthy, based on a set of norms and rules that individuals and their families must follow. Thus, health has a conception based on the administration of programs, services, and actions that regulate the behavior of individuals and specific population groups to reduce risk factors that compromise health and promote and establish healthy habits and lifestyles:

“Introductory approach to Public Health. Sources of morbidity and mortality data. Population dynamics. Vital statistics and health indicators. Incidence and prevalence” (PPC 5).

Starting from this, by emphasizing theoretical-practical frameworks based on the Public Health model during health training, Psychology ends up focusing solely on expanding its scope of action in this area. Its practice relies on the normativity of actions developed from a bureaucratic and informative bias. Thus, it focuses on the development and applicability of instruments that encompass a larger number of people but still remain centered on the etiological agent of an individual and privatist order, even when adopting prevention and health promotion biases (Souza, 2014).

Regarding the practices addressed during the training process that encompass the Public Health model, these focus on expanding the hegemonic clinical model to the social realm to cover a larger number of people, based on health practices from a multidisciplinary perspective:

“Diagnosis and intervention in Public Health. Planning, execution, and evaluation of interventions characteristic of the psychologist’s professional practice in Public Health” (PPC 28).

By focusing on presenting instruments during Psychology training that prioritize isolated actions based on traditional and descriptive epidemiology, this process is restricted to theoretical-methodological frameworks limited to working methods characteristic of Public Health. Consequently, Psychology training centralizes its actions on the biological conception of health through the development and participation in specific health campaigns, disjointed from other sectors (Education, Social Assistance, Security, among others) (Souza, 2014).

Regarding the ethical-political guidelines of the curricula encompassing the Public Health category, these concepts were limited to normative discussions through booklets, statutes, and codes that encompass the field of civil rights and duties:

“1988 Constitution. Statute of Children and Adolescents. Rights policies for children, adolescents, and the elderly. Possibilities of professional practice in rights policies” (PPC 3).

Given this perspective marked by the emphasis on an illusory professional neutrality regarding political and social causes, binary constructs are created in the Psychology training process, separating subject and object, interior and exterior, individual and collective, clinic and politics, clinic and collective health, and ultimately, Psychology and Politics. These divisions promote conceptual notions expressing these categories as dialectically opposed, distant, and naturally different, aiming to confer a degree of scientific validity to Psychology (Bernardes & Guareschi, 2010).

26.4.3 Collective Health Model

This category had the following representation in the curricular components of the 30 investigated Course Projects: on the one hand, of the total 727 analyzed disciplines, we identified only 16.4% (n = 117) of the text components; on the other hand, of the total 727 syllabi, we identified 33.33% (n = 241); and of the total 428 references, we identified 56.5% (n = 243) of the text components related to the titles of works as belonging to the Collective Health field.

Scarcelli and Junqueira (2011) state that the Collective Health field seeks conceptions about the health-disease-care process that go beyond the boundaries of the biomedical model, marked by the emphasis on disease. Therefore, they understand this process as the result of a set of physical, psychological, and socioeconomic factors to which individuals are subjected:

“Health management in Brazil. SUS and the Family Health Program. Integral care in Collective Health. Professional performance in public health policies” (PPC 1).

For Paim and Almeida Filho (1998), the importance of this broad understanding of the health concept encompassing the Collective Health field is to recognize that there is more than one truth, and these assume different positions depending on the social needs of the territory, i.e., the aspects related to the social determinants of health. Therefore, building health training in Psychology from intersections with the Collective Health model promotes the adoption of pedagogical strategies that go beyond the traditional teaching-learning model. Consequently, there are no considered correct ways of doing or ideal training models, but processes marked by conceptual and practical guidelines created and recreated based on the needs of each local reality in which these courses are embedded (Scarcelli & Junqueira, 2011).

Regarding the practices addressed in the analyzed curricula that encompass the Collective Health model, these focus on the social health needs, using material and immaterial technologies and actions centered on different social groups and territories (Paim & Almeida Filho, 1998):

“Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention issues. Familiarization, Territorialization. Demand Survey and Intervention Planning. Identification and Prioritization of Needs and Resources” (PPC 7).

These results support Paim and Almeida Filho’s assertion (1998) that the “tools” of the professional in Collective Health are produced from the organicity of actions and socially constructed. Thus, according to the authors, these actions promote a dual role for the professional: that of a technician of health needs and in the management of health work processes, including clinical practice management, or even the management of services and work through sectoral health networks and intersectoral public policies present in the territory.

Regarding the ethical-political guidelines addressed in the curricula encompassing the Collective Health category, these, in addition to covering technical, economic, and ideological aspects, involve a profession project linked to the emancipation of human beings through a set of concepts and practices focused on social needs:

“Possibilities of professional practice in rights policies. Psychology and the field of rights. Psychology and social commitment. Culture. Politics. Society. Ideology. Democracy. Power. Social movements and citizenship” (PPC 28).

Birman (1991) highlights this ethical-political dimension by pointing out that the naturalistic medical discourse has always marginalized the political dimension of health care. Thus, Collective Health would be one of the alternatives for restructuring the health field and Psychology itself concerning this field, by emphasizing ethical, political, and symbolic dimensions in its theoretical-conceptual guidelines, while relativizing the hegemony of the anatomical-physiological discourse without disregarding its importance in professional training.

26.5 Final Considerations

In general terms, when analyzing how Health and the Collective Health field constitute Psychology training based on the investigated courses, we observe advances, especially in the curricular scope. In this sense, we can highlight the emphasis given in syllabi, especially regarding bibliographic references, to theoretical-methodological and ethical-political guidelines related to the Collective Health model, which are quite pertinent and aligned with the current debate. However, the traditional Public Health field and the Biomedical model still strongly underpin the training processes with concepts, models, and practical guidelines for health work.

Therefore, it is necessary to break with curricular proposals that reaffirm vertical architectures, that is, defined a priori solely by administrative and technical instances without considering local realities. It is urgent to articulate practice scenarios where courses are in harmony with services and the dynamics of the general population, including strengthening interdisciplinary and interprofessional training, as well as competencies focused on managing work processes of teams and between services if we want to advance with more well-qualified training to work based on SUS (Batista & Gonçalves, 2011).

Finally, we understand that the theoretical-epistemological, technical-operative, and ethical-political foundations of the broad health discussions under the perspective of the Brazilian Health Movement and Collective Health need to be expanded and strengthened in the training processes of undergraduate Psychology courses, including emphasizing interprofessional training, so that our science and profession can advance in this field as a potent and articulated knowledge core with others, capable of offering more resolute, integral, and continuous care actions, full of innovations and transversalities that increase the resistance to continue supporting the Unified Health System, even amid the privatist logic that falls on Brazilian Public Health.