38 “We” Between Scribbles and Words: The Creation of a Comic Book for Public Policies with Vulnerable Youth

38.1 In the Beginning, There Was the Draft

Currently, there are approximately 7,139 languages spoken around the world (Ethnologue, 2016), 7,139 different ways to express, share information, describe, write, and inscribe oneself in the world. We begin by talking about languages, even though this is not a chapter about that topic, but rather about a way of inscribing oneself in the world that transcends the standard written language typical of academia. As Duarte Júnior (2000) proposes, we must dare within academia, bringing new languages to dialogue with everyday life.

Language, in itself, expresses the variety we have as human beings. If our history is built through this diversity, why deny it precisely when we talk about science and education? More than that, as a space for dialogue and encounter, especially through public access policies, we cannot think of universities without thinking of difference. So, why not create new contours within the university?

For the research project “‘Music is Just a Seed’: Art and Education as a Tool for Empowerment for Marginalized Youth,” we initially planned the organization and implementation of art workshops aimed at raising awareness of social issues common to socially vulnerable youth, users of the Social Assistance Reference Center (CRAS) in the city of Reriutaba/CE, through discussions about music, dance, poetry, etc. The workshops were to be developed within the Service for Coexistence and Strengthening of Bonds (SCFV) at CRAS Amanaiara, where the researcher worked as a psychologist. The intention was to observe how art could impact these youths to develop a sense of empowerment and social transformation.

However, life has its own course. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, group workshops became unfeasible. Even considering a virtual workshop, access barriers emerged, as many target youth did not have cell phones or internet access at home. Thus, the virtual option would result in exclusion rather than inclusion, contrary to the workshops’ goal.

Therefore, amid research orientation dialogues, the production of a booklet or a comic book (HQ) was discussed as a facilitation tool for working on topics relevant to Brazilian youth’s daily lives (racism, sexuality, gender, violence, family relationships, and other affective relationships), which are often difficult to discuss due to the density and complexity of these topics. The material would support professionals working with youth, offering opportunities for discussion on various topics and allowing youth to express themselves through art. This art could manifest in the tool through format, content, or both via illustration, music, and design.

We opted for the second option, not only for the appeal to the youth language that the HQ would provide, being more accepted by CRAS users, but also for the possibilities considered here of connecting with these youths’ lives through a narrative that dialogues with the experiences common to peripheral youth, often lacking relevant space in the media. The HQ could bring to the forefront issues that Brazilian youth, especially those from the peripheries, face daily, such as gender, race, and class issues, often silenced and invisible as they do not appear in mainstream media or only as secondary issues.

Thus, the HQ takes shape, constructing the narrative, characters, and spaces that resemble real stories since the researcher creates it from work experience at CRAS with the youths assisted by the institution. The traits are borrowed from reality and transcribed into a storyline that brings these youths from the background to the forefront, allowing a new perspective on a reality written daily in the lives of Brazilian youth.

38.2 Some Line Arts of Brazilian Youths

To create the HQ, titled “We”1, it was necessary to combine complex issues of race, class, mental health, gender, sexuality, diversity, and equity with a youthful, accessible, and relevant language to ensure interest and identification of the target group we hope to reach with the story. Considering that our interaction with artifacts is laden with judgments, values, and beliefs from previous experiences, memories, and indirectly obtained information (Cardoso, 2013), it was crucial that the production did not depart from the researcher’s position as a CRAS reference technician in his experience within the institution.

Within CRAS, there was an opportunity to actively participate with social counselors in activities with the SCFV youth, where exchanges, dialogues, and conversation circles took place. Experience showed that in these dialogues, we could get to know part of the youths’ perspective on their surroundings and identify issues that brought them together. From the HQ proposition by the research, the researcher inhabited these spaces of speech and listening attentively to what could compose the storyline of ‘We.’ The concern was to create a story pertinent and consistent with that youth’s perspective, addressing the emerging issues with new representations that ensured the youth’s representation in the main characters without giving the impression of exposing their privacy.

Thus, the work ethically committed to creating characters with common stories based on the youths’ experiences, without using their statements literally or exposing them. This was extended by the researcher’s own youth experience and observation of other everyday stories found in the media, social networks, and daily life, not solely focusing on CRAS youths but articulating them with different Brazilian youths.

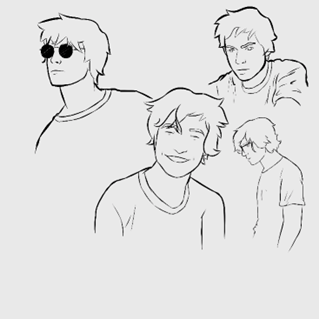

Consequently, the characters’ outlines reflect the various realities found among Brazilian youth, with real, harsh, and fun stories converted into a narrative with one foot in reality and the other in fiction. This led to the creation of Liz, Caiubi, Luke, Julia, and Oliver, carrying marks daily inscribed on real people surviving the barbarism of neoliberalism (Abramo, 2008). These barbarisms result from experiencing violence mainly related to stigmatization of marginalized places, whether concrete or not, such as racism, homophobia, sexism, and violence in social relations, both in intrafamilial spaces and public spaces, such as schools.

Caiubi is a bisexual youth of indigenous descent who hides both traits at school because he feels the need to prove his masculinity, as he sees himself as “the man of the house” since his father’s abandonment. He dates Oliver, a gay teenager who recently moved to a new city and school due to his mother’s job change. Oliver is best friends with Liz, a proud black, plus-sized young woman who hides trauma caused by racism and fatphobia behind humor. Upon arriving at school, Liz and Oliver meet Luke, a transgender youth who has recently started his transition process and has not found the courage to tell his mother, fearing expulsion from home. Luke is also new at school and, upon arrival, meets Julia, a white teenager who takes feminism seriously but from a perspective that does not consider race and class issues, leading to clashes with Liz.

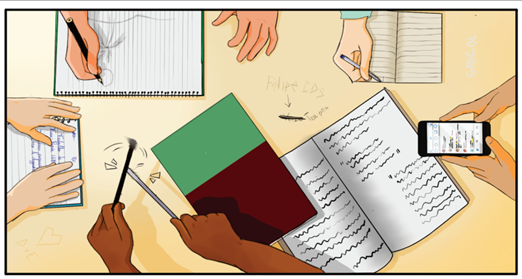

These youths end up in the same group for a Portuguese assignment. However, their union as a group only emerges through sharing their differences, highlighting points of convergence and divergence but, above all, support. From the point where “they” transform into “we,” the creation of bonds allows support beyond the school experience; the “we” opens up the idea of community.

Thus, both the characters and the relationships among them allow access to different relevant discussions in the youth’s daily lives. Liz and Julia present issues about feminism, racism, aesthetics, and mental illness experienced through social exclusion or family toxicity. Moreover, although not directly addressed, their relationship also touches on self-harm and depression.

In turn, the relationship between Oliver, Caiubi, and Luke addresses masculinity, homoaffective relationships, sexuality, and gender issues, opening up thoughts on both transgender identity and gender performance associated with masculinity and its power positions. Additionally, this encompasses violence stemming from homophobia and sexism.

Furthermore, in the HQ, these issues appear not only in discussions among the youths, but secondary roles also present power dynamics. For example, when teacher Bel invites the youths to bring their daily lives into the classroom through an activity for a second grade, this breaks the barrier between school and external experiences. Another element is the principal’s character, who occupies a silencing position towards the youths, demonstrating a lack of interest in their relationships, conflicts, and emotions.

Another noteworthy aspect is the characterization of primary and secondary characters, as well as spaces, considering regional and national representation. This choice materializes in the HQ through language, the use of neologisms, the predominantly non-white primary and secondary characters, and the presence of bars—common marks in our public objects and buildings—in the physical structure of public schools. Thus, it is through presenting the perceived reality that the boundaries of the real experience of Brazilian youths, specifically peripheral youths, and fantasy are blurred, allowing pathways for transformation.

To build knowledge and transform action into revolution, it is necessary to understand the colors the listener uses to paint the world so that we can present new paintings, techniques, and colors (Freire, 2019), thereby joining forces for the radical transformation of social oppressions that persist. As Preciado (2020) states, “for the subaltern, speaking is not simply resisting the violence of hegemonic performativity. It is, above all, imagining dissident theaters where it is possible to produce a new performative force” (p. 131).

Ferreira (2010) notes that art is a specific way of building knowledge, an inventive force that recreates life. Therefore, fantasy broadens our field of vision and creates tools and mechanisms for structural societal change. Creativity allows us to transform our reality, as imagination enables us to trace new routes that impact concrete reality, making it suitable for the space of education and politics (Freire & Shor, 1986). This engagement in making that ties the imaginative to concrete reality points to the social revolution of everyday know-how.

38.3 “Who Tells a Tale Adds a Point”: Do All Points Count?

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (2019), in her talk about the danger of a single story, discusses the impact of telling stories about a group or people, constructing stigmas that relegate subjects to inferior or dangerous positions based on how, when, by whom, and how much they are told. This repeats itself in our history and remains present today, as observed in the construction of villains and heroes by the national media.

Adding to Adichie’s perspective (2019), thinking about stories is thinking about power. As Almeida (2015) says, recalling Walter Benjamin, the official, told history is the history of the victors. Wars are told from the perspective of those who win, not those who are defeated, thus legitimizing the lens that views history from the perspective of those in power. Having the power to narrate is having political power. In Boal’s words (2009): “The semantic struggle is a struggle for power” (p. 70). This daily reproduction is rooted in our form of societal construction. When we think about health, education, social relations, and public policies, we notice they are always intertwined with the perspective of those with more power, as they are the ones who construct them. However, their maintenance thrives on the openness they find in our reproduction of this viewpoint in our actions, values, and thoughts.

Therefore, it is undeniable the potency of creating spaces for these “unofficial” narrators to resist the hegemonic speech and hack the processes of social construction, in which, practically, we are all implicated. Thus, creating spaces for listening and speaking is opening fertile ground for new meaning productions and transforming not only individuals but also collectives—and society—through the power of the narrator who metamorphoses into different voices. A narration that is not complete, as that would be unfeasible, but prismatic, meaning it does not hierarchize vertically nor order horizontally but intersects.

Joice Berth (2019) addresses this issue when talking about silencing, using the term “pernicious ignorance,” which refers to bad-faith ignorance that acts violently by hindering or denying access to cultural and intellectual production of historically oppressed groups. “This ignorance arises from the dominant classes perpetuating inequalities and fighting against losing the hegemony of the single discourse” (Berth, 2019, p. 58).

Thus, history and culture, although collectively constructed, are presented only from the dominant group’s perspective. Meanwhile, the other participants in this construction, essential actors in the cultural construction of the country, have their narratives treated as exotic and only find openness at specific historical points, almost as if asking for permission. This can be seen in presenting indigenous or original populations, Afro-Brazilian, and originally Oriental cultures. Berth (2019) also calls this epistemic violence, as it refers to the transmission and production of knowledge, something that also becomes an issue for Preciado (2020), who, during the Flip festival, challenges us to consider the importance and possibility of creating a multiaxial epistemology capable of dealing with the world’s plurality.

Returning to Preciado, we find a path to his question by stating that “what Benjamin invites us to do is write history from the perspective of the vanquished. Only through this inverted rewriting will it be possible to interrupt the repetition of oppression” (Preciado, 2020, p. 118). It is in the profanation of historical tradition that we can rewrite society alongside the excluded and silenced. With them, we can (re)learn new paths for science, education, and public policies.

This path is where the HQ “We” treads and proposes to be a tool for transformation. Although the story is not written and manually produced by the CRAS youths, the storyline brings experiences and realities close to these youths, based on an attentive observation and listening to their lives, using their language and everyday settings. In this sense, the work presents itself as an invitation to speak. It invites the subject, through illustrated theatricality, to look at themselves and their community and understand that their stories deserve attention and written records. It is an invitation to listen to new stories and, why not, to construct new stories from a new perspective.

This process is not distant from educational practice. According to Silva (2000), the act of educating is a way of inscribing difference in the world that brings life by preventing its eternal reproduction. In this measure, education is understood beyond its formal dimension, as differentiation and identification processes transcend the school space, occurring in various places, including CRAS.

As Brazil’s education patron Paulo Freire (2019) states:

If it were clear to us that we learned to understand teaching as possible, we would easily understand the importance of informal experiences in the streets, squares, at work, in school classrooms, in playgrounds, where various gestures of students, administrative staff, and teachers intersect full of meaning (pp. 44-45).

Thus, we understand that education goes far beyond repetitions and training for assessment responses. Education involves affection, relationships, autonomy, and power, something that often goes unnoticed by most of us during our formative process throughout life. It is not uncommon to see education through a superficial prism, reducing it to technical training and market logic, even though its fundamental role in citizenship formation is marked in official documents about education (Severiano, 2021).

Therefore, new ways of doing education inside and outside classrooms are essential, education built in everyday life, in the “poetry of daily life,” as seen in the HQ, contrasting with rigid, harsh education that separates the place of science from the place of fun. Thus, writing with voice and body, color, and history is relevant for education and public policies. As Hooks (2020) states, if we act as if history does not matter or impact us, we risk erasing ourselves. By erasing our bodies in favor of directive and objective knowledge and practice, we erase our social differences and their impacts on our lives under a false assumption of neutrality, which is convenient for neoliberal logic, perpetuating privileges.

Not far from this, public policies are impacted by the reality of the neoliberal society in which they exist, where policy formulation and management face a struggle against the guarantee of social rights. As Teixeira (2009) states:

Formulating social policies in capitalism, and more so in the context of neoliberalism, is facing powerful social forces always fighting to ensure the consolidation of their interests and privileges in the State, which invest against social rights, especially those with a redistributive perspective. (p. 8)

Thus, decision-making positions and deliberation tend to be influenced by market desires over the social needs of the impoverished population. This marks the formulation of public policies in Brazil throughout its history, encountering bottlenecks in both the architecture of democratic participation in policy formulation and the state’s authoritarian view of citizens (Teixeira, 2009).

In this false participation or lack of awareness of the issues affecting individuals impacted by public policies, exclusion occurs through inclusion, whereby the individual assisted by public policies receives a monochromatic logic that considers a generic subject, based on a distant, objective view of people unrelated to those concretely served. As a result, the policy sometimes loses its meaning because it does not make sense to the users.

If public policies lack democratic participation, this extends throughout, including its tools. When establishing the possibility of creating tools from other forms of observing the experience in their spaces, giving voice and opportunities to users and the creative potential of professionals involved in institutions, policy reconstruction can be considered.

Therefore, the HQ as a tool for public policy produced by a CRAS technician embodies both a strength and a limitation. This is because the research field for its creation is present directly due to the professional experience with youths and personal experience as an individual who experienced vulnerability outside the norm. However, the story was not passed through the filter of these CRAS-assisted youths due to the public health circumstances posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. This propels the need for subsequent research focused on analyzing the perception of impacts and meanings produced by the story and characters on peripheral youths and, based on findings, adjusting the HQ.

Nonetheless, this necessity does not obscure the potential of this tool within public policies when discussing voice and history recovery. As Adichie (2019) states, “stories have been used to dispossess and malign, but they can also be used to empower and humanize. They can break a people’s dignity, but they can also repair that broken dignity” (p. 16).

The HQ narrative thus presents itself as a space for creating bonds through dialogue, something inherent to artistic expression. This, as a tool for building bonds, acts from the expression of subjects’ individuality, allowing connection points and the potential to develop a sense of belonging and sociability (O’Neill, 2015).

Additionally, if art welcomes multiplicity through polysemy, playing with the obvious, and expanding boundaries (Gomes, 2015, p. 109), it is through the HQ story that the complexity of youth experiences, so plural, is presented, creating different openings for identification with future readers who can insert themselves into the story and, through its ink, perceive new ways to recolor reality by turning to their own world.

Through the subjectivity involved in constructing the story, readers can recognize themselves, not just as spectators but as those protagonists, borrowing the characters’ traits and colors in “We.” Thus, the We extends beyond the story’s characters, reaching all those who participate in the narrative through identificatory traits. This proximity opens space for liberating one’s voice, essential for considering empowerment. In “Raising the Voice,” Bell Hooks (2019) states that

For the oppressed, the colonized, the exploited, and those who stand and fight alongside, an act of defiance that heals, that enables new life and growth. This act of speaking, of “raising the voice,” is not a mere gesture of empty words: it is an expression of our transition from object to subject – The voice liberates. (p. 29)

The voice inscribes us in the world, allowing us to oppose the demands of another. In other words, raising the voice is a form of emancipation aiming at empowerment, understood here as necessarily linked to the collective dimension, as “critical consciousness is an inseparable condition of empowerment” (Berth, 2018, p. 53). The HQ follows its path without losing sight of this collective condition, as it is through moments of exchange and dialogue between characters that individualism is broken through sharing pains, doubts, and joys previously enclosed in each individual’s experience.

Through encounters and conversations, convergence and divergence points emerge, initiating the construction of a collective, a “we.” From this encounter, previously solitary and silent issues can be redrawn with the support acquired in building bonds.

Fostering spaces for dialogue within public policies, using art as a mediator, contributes to realizing effective citizenship and social reconstruction by traditionally marginalized actors. Through collective experience exchanges, it becomes evident that various existing systems of domination are not the only possible way (Berth, 2018). Instead, we can jointly produce ways to confront them with our communities.

Creativity is essential in this process, whether for its utopian character (Duarte Junior, 1995) or its openness to difference. Proposing a tool marked by art to mediate experience exchanges distances us (although it cannot eliminate the danger entirely) from conducting actions in a merely technical way, which, by its impersonal nature, homogenizes people by not recognizing their plurality.

Consequently, actions in public policies that intertwine art and social themes tend to foster empowerment by enabling the elaboration of subjective issues, critical thinking about the daily life and experiences of the individuals involved. By promoting creative environments, they strengthen individuals and their groups, generating spaces where the individual can take charge of their story, tell it, and rework it.

38.4 Possible Ways to Use It:

As a public policy tool, the HQ is not limited to social assistance policies. Its diversity allows it to circulate through different policies: culture, by considering art’s role in youth construction; education, by walking through the idea of education happening inside and outside the classroom; health, by shedding light on the mental health impacts of social exclusion through racism and body relations. In short, the work can be used in any space where work with socially vulnerable youth is developed around different themes, beyond those exposed here.

For example, we invite readers to imagine a CRAS or school professional wanting to address discussions about social exclusions experienced daily. Initially, the comic book can be handed out to each youth for collective or individual reading.

Following the reading, a conversation circle is promoted, where youths can share what touched them during the material reading, what impacted them, what resonated with their realities, and what, although distant, seemed interesting. In the circle, the idea is to open space for speaking and listening, mainly among the youths, so they can perceive congruence points where the stories touched the same place. It is also interesting to observe characters of identification and the reasons for this, as it allows learning more about the youths and their interests, enabling future actions.

Another important point in the circle is for the professional to understand where the youths are coming from, what violence they have experienced, and how aware they seem to be of it. It is essential for public policy professionals to be aware of positions of privilege and inequality to guide their actions. Matthews (2015) identifies three main consequences for educators who disregard privilege in their work: marginalization, exclusion, and “colonized consciousness.” Here, it is believed that these effects extend to other public policy actions, where exclusion and marginalization occur by erasing or silencing the lived and cultural production of groups. Thus, their interests are not explored, potentially affecting their desire to participate in spaces (Matthews, 2015).

Moreover, this disinterest in these groups’ work can develop a notion of valuing only a particular culture related to privileged groups, to the detriment of their own, assuming an attitude of subordination and affirmation of inferiority by being outside this superior culture, inferiorizing themselves in identificatory and unconscious, cultural, and social processes, understanding themselves as part of an inferior group (Berth, 2019; Matthews, 2015).

Therefore, it is important for public policy professionals to reflect on the notion of privilege and oppression and, more than that, to perceive in their daily lives the relationships around them and the behaviors reproduced by themselves and public policy actors. Here is another possible use: the HQ can serve as a tool to problematize these issues with public policy professionals and youths.

Another alternative is, from the conversation circle, to encourage youths to seek out these characters in real life, inviting them to bring stories that could belong to these characters to the space. These could be personal stories of the participating youths, friends, family members, or distant individuals, like artists. The idea is to show that those stories happen in real life and deserve to be told, that they have value. Additionally, this opens the door to authorship and representing one’s own story.

Other possible uses can also be listed, such as creating sketches or other forms of performance about the story. Another option would be for youths to write stories about other fictional youths in the city where the HQ story takes place, in the shown spaces, interacting with the original characters, crossing paths with them at school, CRAS, streets, or neighborhood. Thus, the HQ unfolds into a space for reconstructing the story by other people, voices, and perspectives.

It is worth highlighting that in these activities, it is interesting for the mediator or facilitator to participate actively, just like the youths, establishing a horizontal relationship in response to the youths’ openness, demonstrating the professional’s interest in establishing a bond not characterized by hierarchy. It is always clear: we cannot transform the world without being with it; acting together gives corporeality to the example and idea (Freire, 2019).

Finally, it is relevant to explain that there are not only these ways of using the material. Limiting its use would be contradictory, given that we start from the idea that there is no single way to tell or make stories. Thus, here we explicitly wish for responsible and free use of the material in the most diverse activities readers engage in. We hope that in the end, it is just the beginning of the path to a recognition and social transformation process for people in their different ways of existing with the world.

38.5 Conclusion Processing…

Returning from the beginning, we can understand the importance of language in our connection with ourselves and the space we live in, in its possibility of transforming reality by how we tell and make history and art. In its unfolding, we are touched by it; we can create identification, and breaches for the entry of previously erased actors. As Hooks (2020) states, it is through language that “we, marginalized and oppressed people, try to rescue ourselves and our experiences through language” (p. 233).

Creating a comic book as a tool for public policy work within a public university is breaking with a hegemonic practice that prioritizes a false division between scientific and artistic practice when both enrich each other in their joint practice. It is understanding the division created between “mind and body,” which erases subjects and the obstacles involving their social place, and reconciling with sensitivity and other subjects with whom we build society (Gomes, 2015; Hooks, 2020).

Beyond that, it creates a practical tool for public policies that not only aims to give space to peripheral youths’ voices but starts from this premise. Thus, using the HQ by public policy professionals contributes to transformative practice, highlighting often ignored but significant experiences, giving youths the chance to see themselves in the characters’ speeches, attitudes, and exchanges.

Creating the HQ implied a broader professional practice, questioning the work space and how it is executed and dictated within public policies. This points to the relevance of alternative technical production for achieving professional master’s objectives. Through research, the researcher can look at their professional experience and act based on it, bringing new action possibilities attentive to meanings. The research also highlights the importance of valuing public policy technicians in their work with vulnerable populations, as this is still a function suffering from professional precariousness, directly affecting services.

Finally, it is hoped that the research does not end here and that it and its resulting fruits promote, increasingly, spaces for exchanges and creation in public policies, where invisible stories find a place to raise their voices. Furthermore, it is hoped that public policies can reinvent themselves for social transformation through democratic means, through many hands, voices, and “we.”

References

The comic book can be accessed through the link: https://forms.gle/WqtWb4vdT38MTw4K7. After filling out the form, created to collect the HQ’s reach, the download link for the file hosted on Google Drive is provided. For more information about the work and access to its content, contact: deninoronhalopes@gmail.com. It is important to note that the work is protected by copyright, so both its sale and distribution without proper credit are prohibited.↩︎