22 Gender Literacy and Adolescents: An Intervention Conducted in the Interior of Ceará State

22.1 Introduction

This text reports on a consultancy carried out through interventions focused on gender literacy in schools. This consultancy was conducted in response to the growing need to address the deep gender inequalities present in society, particularly in the educational context.

The demand for interventions related to gender literacy becomes evident in light of issues highlighted by recent studies, which emphasize the importance of addressing gender disparities to combat violence against women (Araújo, 2008) and the negative impacts of sexism on men’s behaviors and emotional skills (Zaiba & Sinha, 2023). This demand aligns with the guidelines of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) on education for gender equality and women’s empowerment, which reinforce the relevance of contextualized educational interventions to promote a more equitable society (UNESCO, 2017).

Aiming to promote gender literacy in schools, the intervention was based on a multifaceted understanding of the concept of gender, which goes beyond the traditional binary. Thus, it explored aspects such as the relationship between gender and sex stereotypes, sexual orientation, and cultural influence in shaping the behavioral repertoire of men and women (Butler, 2012; Marques, 2021; Skinner, 2003; Zanello, 2018).

In this regard, gender is considered a social construct that perpetuates privileged pathways of subjectivation in Western society (Marques, 2021). Thus, patriarchy emerges as an ideology that sustains the power difference between men and women (Lerner, 2019; Saffioti, 2015). Gender inequalities manifest in various spheres, from everyday situations of violence to disparities in the labor market (Guerin & Ortolan, 2017).

Understanding the cultural patterns that perpetuate gender inequalities is fundamental for directing effective educational interventions, among which gender technologies stand out: mechanisms that drive the learning of behaviors supposedly intended for men and women, such as movies, soap operas, games, among others. These technologies culturally shape the being of men and women and directly impact the formation of gender stereotypes, contributing to the unequal power relationship between men and women that perpetuates across various spheres of society (Lauretis, 1994).

To reduce these inequalities, one strategy is to introduce gender discussions in the school context, as the school, as a social apparatus, plays a crucial role in reproducing or deconstructing these norms (Eugenio & Jardim, 2020; Jardim & Abramowicz, 2005). The school, by committing to promoting educational actions aimed at non-sexism, can significantly contribute to reflection and cultural change. This insertion, supported by the National Curriculum Parameters (PCNs), should be carried out in a dialogical and participatory manner, recognizing the school as a democratic space (Alves, 2018; Rena, 2006).

Authors exploring the relationship between gender and education emphasize that the school acts as an influential agent in forming individuals and reproducing inequalities. Markers such as the separation of boys and girls in school activities; the books available in the library, where romance and poetry are intended for girls and action and adventure for boys; the institution’s sports court, generally used by boys for sports practice; and the organization of the school’s physical spaces all contribute to unequal learning processes (Louro, 1997; Moreira et al., 2021).

Among the pedagogical initiatives to deconstruct gender norms, it is suggested to create discussion groups, include content on gender and sexuality in school curricula, and organize mixed activities. Also relevant is the training of teachers sensitive to gender issues (Soares, 2003). Regarding experiences of interventions that relate gender and education, activities with teachers and students aimed at changing perceptions about gender and reducing levels of prejudice can be mentioned (Alves, 2017; França & Calsa, 2012).

Thus, this consultancy aimed to promote gender literacy in middle school. It is expected to contribute to advancing gender equality in society.

22.1.1 Gender Literacy in Schools

In the realm of gender literacy, it is essential to consider the influence of social discourses that permeate the construction of gender identities. In this context, literacy practices play a crucial role in deconstructing stereotypes and promoting inclusive and equal education. Addressing gender in the school environment is not just about transmitting information but requires creating pedagogical strategies that stimulate critical reflection on the social constructions of gender (Louro, 2000).

Moreover, it is necessary to address the multiple dimensions of identity, such as race and class, in constructing gender literacy practices in schools (Zanello, 2018). This construction, therefore, should not be dissociated from an intersectional vision, recognizing the different forms of oppression and discrimination present in society.

In this sense, some pedagogical initiatives can be implemented in schools to deconstruct gender and sexuality norms: forming discussion groups for sharing experiences among students; modifying school curricula and teacher training to promote sexual and gender education; debates on sexual diversity, conducting mixed activities, and including LGBTQIA+ characters in activities such as plays (Soares, 2003). Thus, the teacher plays a crucial role in creating an educational environment that promotes respect for gender diversity. Continuous training of educators, coupled with a reflective attitude, is essential for the successful incorporation of gender literacy in the school curriculum (Scott, 1995).

In summary, constructing gender literacy practices in schools demands a comprehensive and multidisciplinary theoretical approach. Integrating intersectional perspectives, participatory didactic strategies, and the educator’s role are key elements for developing an inclusive school environment aligned with gender equity principles.

22.2 The Intervention Conducted

22.2.1 Initial Visit to the School, Proposal Dissemination, and Signing of Consent and Assent Forms

The intervention was carried out in a full-time public school in a city with approximately 20,000 inhabitants, located in the interior of Ceará state, between August and October 2022. After prior contact with the school’s management team, a visit was scheduled to formalize the partnership. During this visit, a brief explanation of the objectives and theme of the intervention, as well as the methodology to be used, was provided. The administrative director and the coordinator of the final years of middle school were present. Both were willing to collaborate and offered the video room and the Wednesday morning slot for the meetings.

It was agreed that the students would be taken out of class during the first two periods (07:00 – 08:40) and taken to the space designated for the intervention. This arrangement was discussed with the teachers who taught during this period, and they all agreed with the system. Concluding the visit, the date for the intervention’s dissemination to the students and the start date of the activities were set.

The following day, another visit to the school took place to disseminate the intervention among the students. On this day, the basic precepts of the intervention and the methodology of the meetings were presented to the students, and doubts about what was addressed were clarified. The students were also informed that the interventions would begin the following week and be held on Wednesdays.

To those interested in participating, an Assent Form was provided, given the students’ age group, and a Free and Informed Consent Form (TCLE), as the intervention was part of a broader study approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the State University Vale do Acaraú (CAEE 53379421.9.0000.5053). The guardians were informed about the procedures the students would undergo and could, at any time, question and clarify any doubts.

It was agreed with the management team and the students that if the guardians felt the need to clarify any doubts, they could go to the school, as the researcher would be there during the first morning period to receive them. No parent or guardian sought the school or the researcher.

22.2.2 Participants

Twenty-five students participated in the intervention, of which 13 were female and 12 male, from the final grades of middle school: 7th grade (4 participants), 8th grade (12 participants), and 9th grade (9 participants). The students were not divided by gender, age, or the grade they were in.

22.2.3 The Intervention Process

The intervention was conducted on the school’s premises in a room reserved by the institution. The students always arranged the chairs in a circle. This was not a requirement of the researcher leading the intervention, but it was noticed that everyone felt welcomed this way, which motivated participation. While the students performed a given task, the researcher walked around the room and answered recurring questions about the task itself.

The group interventions were divided into five structured meetings following the proposal of França (2012), each addressing a theme related to gender: a) activating the participants’ prior knowledge about the themes; b) explaining and justifying the group’s understanding of the theme; c) problematizing this understanding; d) raising alternative concepts to those identified in the previous stages; e) provisional conclusions of each session. Each meeting lasted 1 hour and 30 minutes.

22.2.3.1 Meeting 1: Getting to Know the Participants

All participants were present at the first meeting, dedicated to introducing the students. For this purpose, the “self-portrait” activity was carried out, aiming to bring

the group members closer together and strengthen the bonds between them and the researcher. Papers and colored pencils were distributed, asking each student to describe their characteristics. This activity promotes a moment of self-reflection on identity and allows for greater closeness with the “other.” Additionally, it involves feelings and creativity, enabling reflection on one’s identity (Maia et al., 2013).

Each participant showed their work to the others, who observed and tried to describe what they saw in the image. The dynamic met its objective, as the students’ engagement showed they could get closer and know each other better.

After this dynamic, information was conveyed, and participants’ doubts were clarified. The previously agreed terms were reiterated. Furthermore, it was emphasized that the researcher would be responsible for guiding the students, picking them up from their respective classrooms, and taking them to the meeting location. This practice was implemented to avoid dispersions on the school premises, thus ensuring the participants’ presence and involvement during the scheduled meetings.

22.2.3.2 Meeting 2: Gender in Music

The second meeting had twenty-three students participating and aimed to introduce and familiarize the participants with the theme of gender. The approach began by questioning the students about the concept of gender, and from their answers, a brief explanation on the topic was given, including the definition of gender, its relevance to our construction as human beings, the difference between gender and sex, and the consequences and impacts that gender stereotypes have on life in society.

Continuing, examples of cultural instruments that reinforce the previously discussed inequalities and consequences were presented. For this purpose, some musical compositions were used, along with the following question: how are gender stereotypes conveyed in the musical compositions we often listen to?

Three Brazilian compositions of distinct styles were selected to illustrate this stage of the discussion: “Estranha Loucura,” interpreted by the renowned singer Alcione; “Vidinha de Balada,” performed by the duo Henrique and Juliano; and “Desconstruindo Amélia,” sung by Pitty. The choice of these songs was based solely on the criterion that they are Brazilian compositions, present diverse musical styles, and contain lyrics that provoke the central discussion of this investigation.

The first musical composition analyzed addresses the theme of male virility and female submission in romantic contexts. Titled “Estranha Loucura,” the song portrays the experience of a woman who perceives herself as “crazy” for being involved in a one-sided relationship, where her actions are disproportionately dedicated to maintaining the relationship while the partner remains passive. She bears the burden of responsibility for the relationship, taking the blame for any disagreements, while the partner is absolved of any responsibility. In this context, traditional femininity standards are represented by the expectation of unconditional understanding and kindness, while masculinity standards are defined by the dependence and humiliation imposed on the woman (Jesus, 2018).

In the second song, male virility is emphasized through sexual expression and the demonstration of strength, highlighting the narrative where the male subject coerces the female figure to love him at any cost. Furthermore, the song perpetuates the idea that the desirable woman for marriage is the one who avoids party environments, maintains a modest demeanor, and refrains from consuming alcoholic beverages. The song’s lyrics subtly disguise violence and normalize behaviors characteristic of abusive relationships, such as forced kisses, rule imposition, and emotional coercion, portraying these actions as romantic and socially acceptable.

The choice of the last musical composition was deliberate to introduce a contrasting perspective to the themes presented in the previous songs. The lyrics of this song explore the process of female emancipation, moving away from the traditional role of women confined to home and family. Instead, the narrative highlights a woman who works outside the home, takes care of herself, and allows herself moments of leisure and fun. This representation challenges the socially imposed roles on women, highlighting the existence of multifaceted female identities beyond historically established limitations (Jesus, 2018).

The students were divided into smaller teams, given printed lyrics of each song, and instructed to discuss the following topics:

- Representation of women in the songs;

- Three problematic behaviors of men mentioned in the lyrics;

- Changes in male behavior intended to avoid these problematic behaviors;

- Changes in female behavior perceived throughout the songs.

The purpose was to investigate the gender dynamics present in the lyrics and identify stereotypes, behavioral patterns, and possible narrative evolutions. The aim was to provide a critical analysis of the conveyed messages.

Additionally, during the activity, the implications of abusive behaviors motivated by gender in forming our individual identity and social dynamics were discussed. Data related to violence against women and its impacts on the process of constructing subjectivity for both men and women were presented to support these discussions. During this interaction, the students not only answered the proposed questions but also shared relevant examples, demonstrating engagement in the activity. It is important to note that at this moment, the groups were spontaneously formed, providing a more fluid and participatory dynamic.

To conclude, a brief summary of what had been discussed was given, and participants were asked what they had learned at that moment.

22.2.3.3 Meeting 3: Gender Technologies

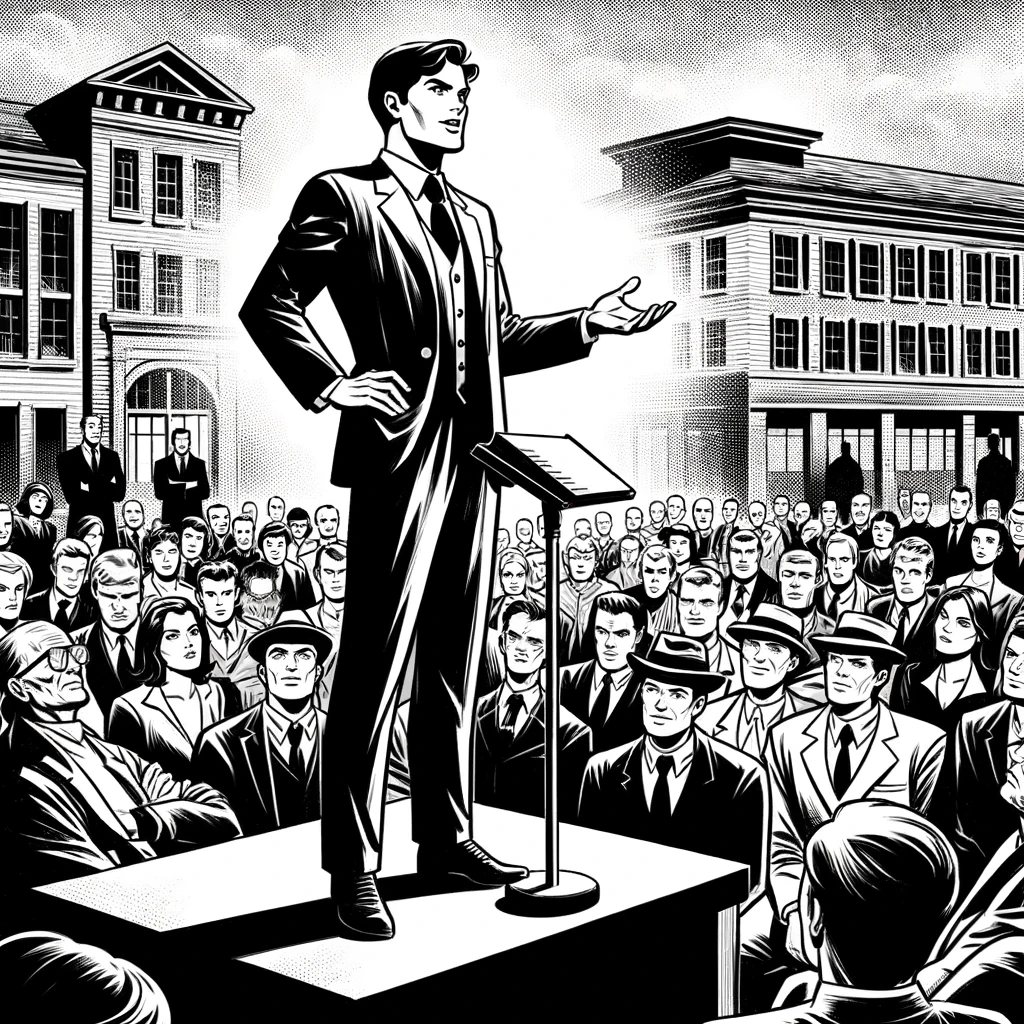

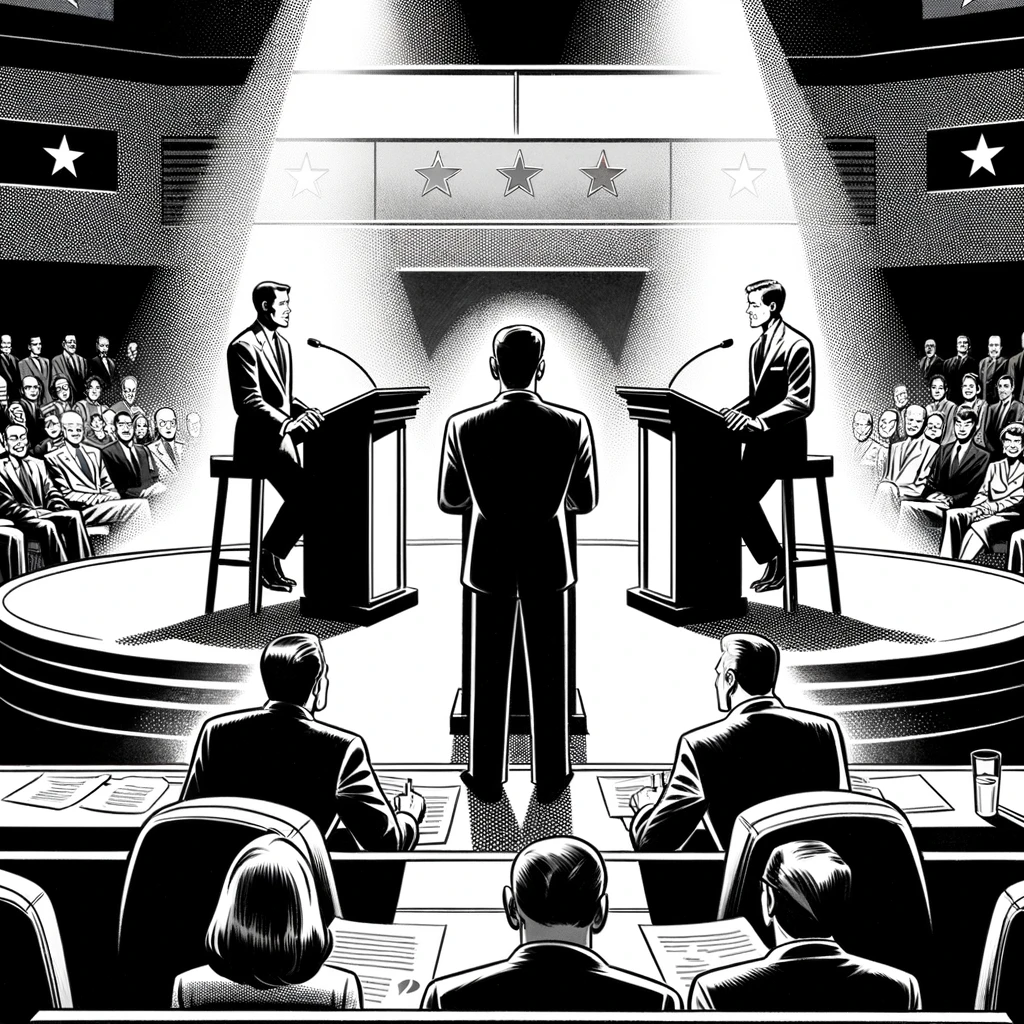

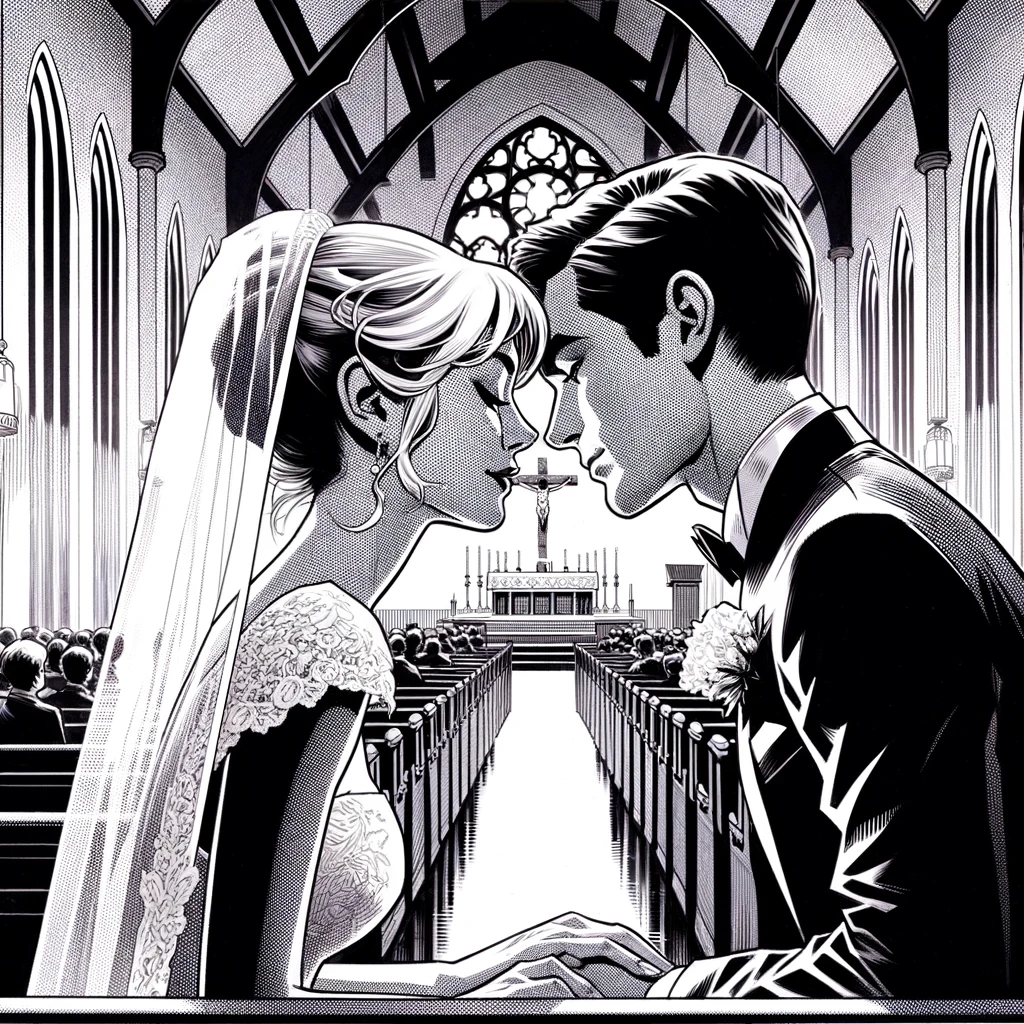

The third meeting had all participants present and began with a review of the concept of gender and key points discussed in the previous meeting. Next, to assess the participants’ prior knowledge, a series of images culturally associated with male and female gender stereotypes were presented. These images were selected to illustrate the ‘oppositions and inequalities’ between genders, exemplifying the devices of love/maternity and virility described by Zanello (2018).

Each image was presented individually, and the participants were asked to categorize them as ‘man,’ ‘woman,’ or ‘both.’ This activity aimed to examine the influence of gender roles on students’ perceptions. At the end, the images were organized into the corresponding groups, resulting in the following categorization:

| Woman | Both | Man |

|---|---|---|

| Representation of silence | Representation of marriage | Representation of physical strength |

| Representation of work with numbers (productive) | Representation of political debate | Representation of power/leadership |

| Representation of weight loss | Representation of alcoholic beverage | |

| Representation of aesthetic procedure | ||

| Representation of romantic love |

Next, an explanation was provided to the group about why certain images are readily associated with women while others are attributed to men. This explanation aimed to contextualize the categorization and understanding the group developed about the theme, providing a deeper insight into these concepts in relation to reality. In this context, it was appropriate to introduce the concept of ‘gender technologies,’ highlighting how images, symbols, and other cultural productions are used in society to reinforce gender norms and expectations, thus influencing our perception and interpretation of the roles of men and women (Zanello, 2018).

To problematize the mentioned concept and illustrate how it manifests in practice, several magazine covers circulating in our country were presented. In the discussion, it was emphasized that the magazine covers featuring women were limited to presenting aspects related to beauty and fitness, conveying the understanding that the “beautiful” and valued woman is thin, white, and has straight hair. This emphasis on physical appearance reverberates in sexual objectification and, consequently, in the daily violence women face. Additionally, the discussion included the issues raised by the covers featuring men. It was noted that men are privileged because, according to what is portrayed on the covers, they are on the “side” where money and professional success reside. It was discussed that a socially valued man is one who financially supports his family and is a conqueror (Zanello, 2018).

After this exploration, the problematization of the understanding the students had developed was conducted. To do this, the students were asked to identify three examples of gender technologies, which could include characters from movies, cartoons, series, soap operas, songs, magazine covers, games, toys, among others. Some responses emphasized the roles of protagonists in soap operas, portraying women in a vulnerable position, constantly seeking romantic love to live “happily ever after.” Other participants mentioned that the villains in children’s cartoons are always “witches,” pointing out that these “witches” became what they were because they were rejected by men for not having a beautiful or attractive appearance.

To conclude the discussion, the central concept addressed in the meeting was reviewed. There were also questions about the main points learned by the participants.

22.2.3.4 Meeting 4: Reversing Roles

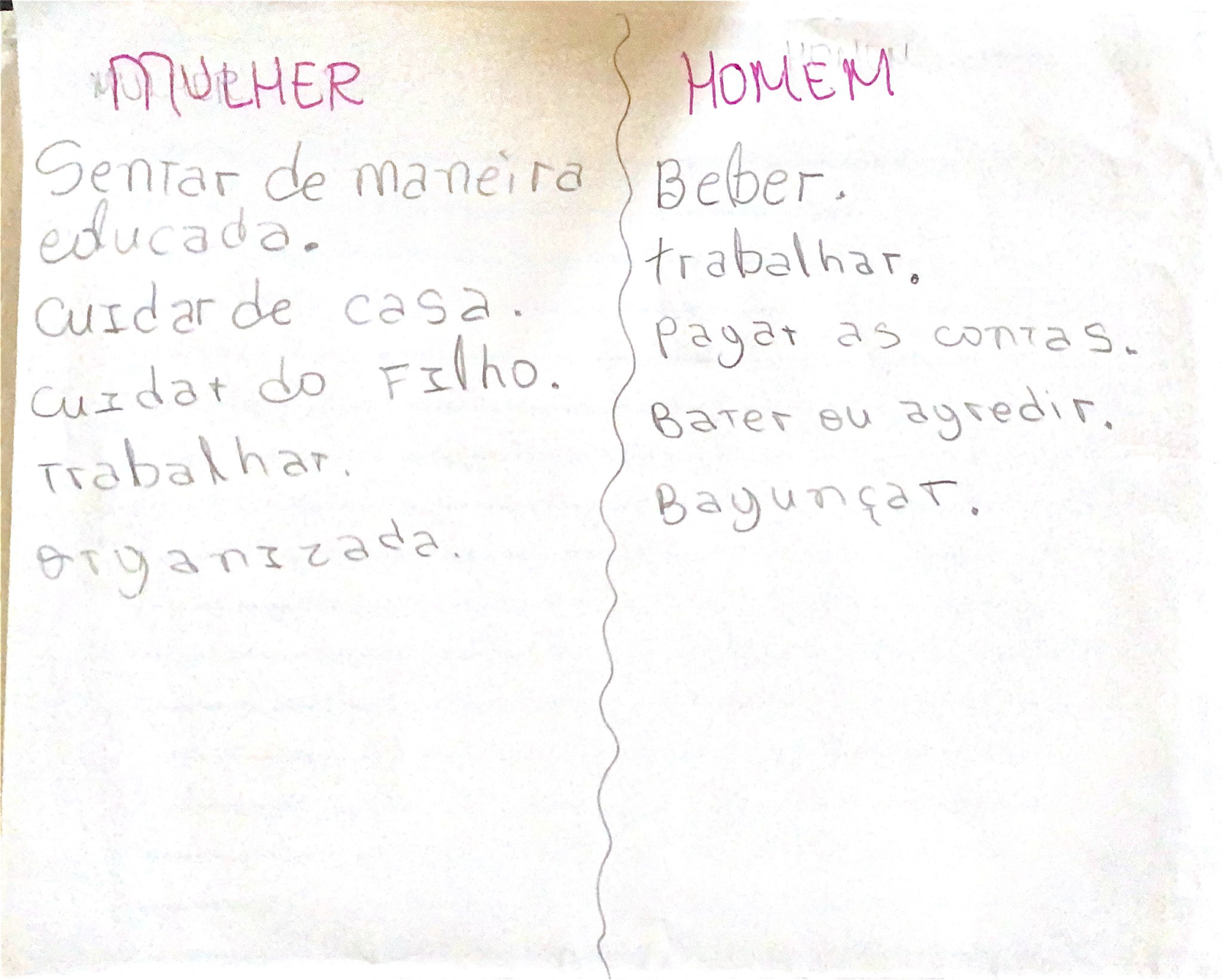

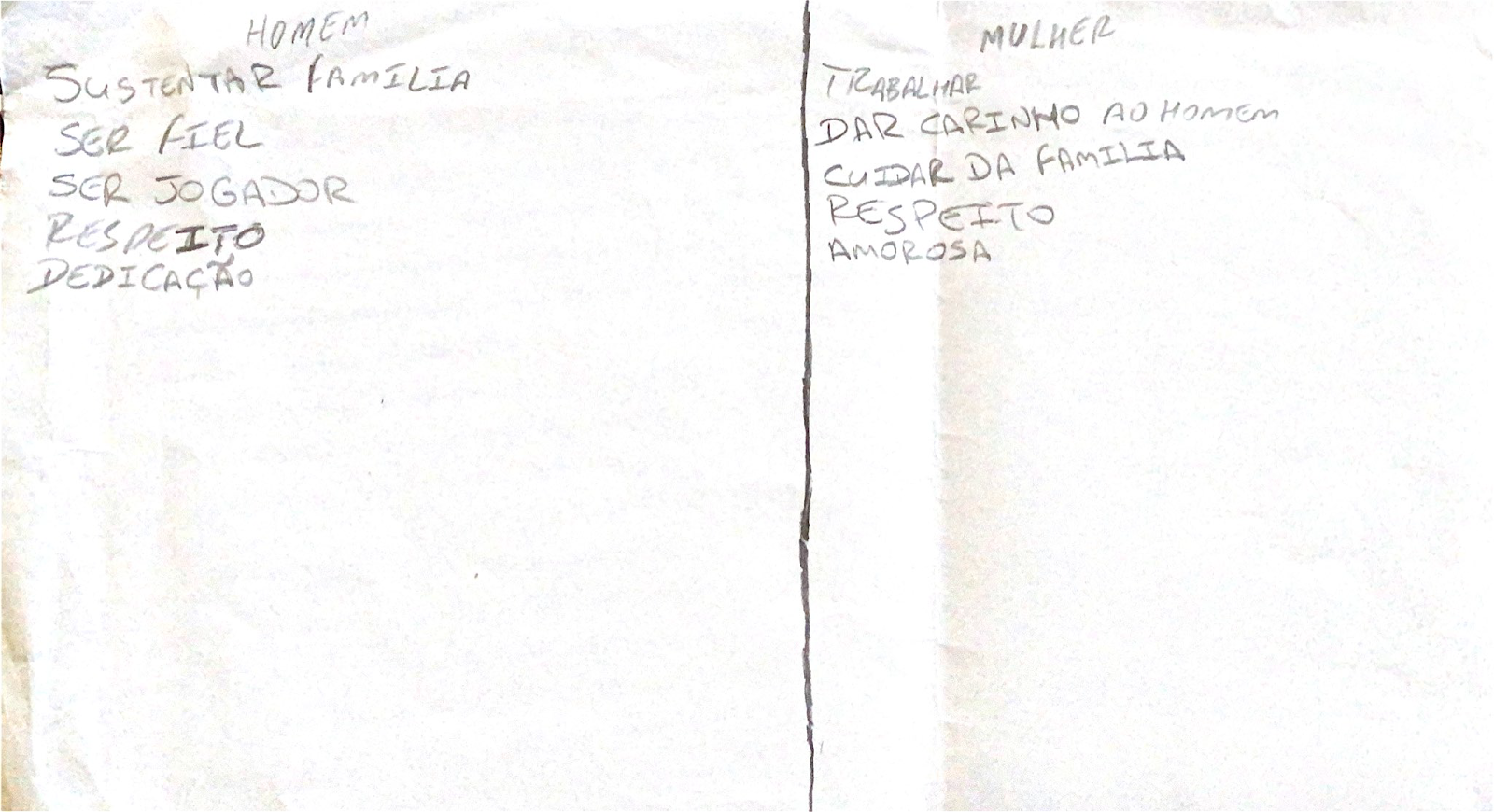

This meeting recorded the presence of sixteen participants and aimed to problematize socially prescribed and accepted behaviors for men and women. To assess the students’ prior knowledge, they were divided into groups separated by gender, with each group receiving a sheet of paper. They were asked to list ten behaviors (five feminine and five masculine) that are often considered appropriate for men and women in daily life. The lists produced by the groups were as follows:

The lists were read and discussed in a large group. To promote participants’ understanding and foster discussion, the concepts discussed in previous meetings, such as gender technologies, behavioral scripts, and gender, were used. These concepts aimed to promote a new understanding, allowing new perspectives on culturally taught behaviors.

The students were encouraged to challenge and question the social roles attributed to men and women. To facilitate this moment, they were invited to reverse roles and represent behaviors typically associated with the opposite sex. Again, the boys assumed behaviors generally attributed to girls, and vice versa.

Thus, the boys’ group represented a woman exercising her profession outside the home and having fun with her friends at a party. It is noteworthy that the mannerisms used by the students to portray a woman were still stereotypical, which was discussed in the group after the presentation. Next, the girls represented a man with violent and aggressive behaviors towards his wife and then an “alternative version,” showing a man who shares household chores

, is present in child-rearing, and respects his wife’s wishes and rights.

Using these representations, we discussed gender stereotypes and pointed out more alternative behaviors and roles that men and women can perform. Here, the concept of gender stereotypes was reinforced (Zanello, 2018). The discussion included several examples, such as professions taboo for women (e.g., football player) and activities related to child care, easily imposed on women.

To conclude, the main points discussed in the meeting were reviewed.

22.2.3.5 Meeting 5: Addressing Gender Inequality

The final meeting had the participation of twenty-one students and aimed to present the main consequences of gender inequality. Initially, participants were provided with news articles related to violence against women as a method to assess and expand their prior knowledge on the topic. The news was read, and the reason behind the presented data was discussed with the students. The issue of gender inequality and its consequences in economic, political, educational, social, and cultural spheres was emphasized, explaining that the absence of women in leadership positions and policy-making prevents improvements in these indices. Besides the data presented in the news, it was highlighted that women earn less than men, often performing the same function, and that unpaid work is mostly performed by women since men occupy leadership positions and engage in paid activities (Zanello, 2018).

Continuing, four concrete situations illustrating gender inequality in practice were presented to the students. They were then asked to reflect on each situation and determine if they were true or false. It was previously confirmed that situations 1 and 3 were true, while situations 2 and 4 were false. It is important to note that these situations were selected from news websites to ensure a solid and updated basis for the ongoing discussion:

- Of the 22 federal deputies elected from our state last Sunday, only 3 are women;

- Higher-paid leadership and power positions are mostly occupied by women;

- Worldwide, there are more girls than boys out of school;

- Most men have a double work shift: they work outside the home and still handle household chores.

Most students were unaware of the truth of statements 1 and 3 and considered them false. Upon discovering their accuracy, they were surprised by the portrayed inequality. Regarding the other situations, participants promptly responded that they were false, justifying that they had seen these statements in previous meetings. This stage served to problematize the concept of inequality and allowed students to think of alternative ways to minimize the political and educational inequality portrayed in the sentences.

Thus, the students were divided into three groups and instructed to think of alternative solutions to mitigate the presented challenges. The alternative solutions proposed by the students are listed below:

- Report cases of violence against women;

- Encourage men’s commitment to equally sharing household chores;

- Talk more about this topic at school for other students who did not participate in this project;

- Elect more women in politics;

- Elect people with gender-related agendas;

- Assume, as students, the duty to use our voice and knowledge to speak about these issues in various places;

22.3 Intervention Results

At the end of each meeting, participants were asked, “What did you learn in this meeting?” Often, the students reported that those moments contributed to expanding their knowledge on the topic and possibly changing their behavior towards situations that provoke gender stereotypes. Some participants emphasized that they “never thought about” the addressed situations and would now start to police themselves to avoid reproducing such stereotypes and reinforcing gender inequalities.

One point that deserves attention is the maternal and amorous device. The maternal device is socially constructed and naturalizes discourses and practices that address motherhood and care as inherently and naturally feminine. The amorous device is defined as discourses and practices that conceive romantic love as a natural and essentially feminine experience. These devices are understood to reinforce and perpetuate gender inequality, as they can be considered a form of power that shapes women’s experiences (Zanello, 2018; Zanello & Porto, 2016).

Historically, the maternal device evolved from the 17th century when the understanding that motherhood was an extension of procreation emerged. Thus, with this understanding, the woman is seen as a “natural” caregiver, and motherhood is idealized as a leap in women’s quality of life (Zanello & Porto, 2016). The following statements illustrate this device:

My dad and I don’t help my mom at home. She does everything by herself. (Student 1)

At my house, it’s me and my brother. My mom only makes me do things and not my brother. (Student 1).

Regarding the amorous device, Zanello (2018) exemplifies that these discourses and practices associating women with romantic love can be elucidated through the metaphor of the “shelf of love.” For the author, women are subjected to this shelf and are culturally taught that their bodies are the great symbolic and matrimonial capital. Thus, there is a need to be emotional, caring, friendly, and loving to “be chosen,” regardless of who chooses them. On this shelf, the ideal is to be young, white, thin, and blonde. Anything that deviates from the “rule” is at the end of the shelf. This makes women extremely vulnerable and subjects them to competition with others. Additionally, this form of love differs from what happens with men.

A friend of mine fought at school because the boy she liked kissed another girl. Instead of talking to the boy, she went to fight with the girl. (Student 2).

To be loved, you have to be standard: thin, cute, straight hair. (Student 3).

The device of effectiveness (laborative and sexual) also deserves attention. The device of effectiveness is linked to the fact that being a man, culturally, means dominating sexual and labor areas. It means being the provider. In other words, masculinity is achieved by displaying strength and sexuality, driving competitiveness and productivity (Badinter, 1993). The appreciation of masculine character happens when a man can support his family and have sexual dominance over his partner(s) (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2013). Thus, denying characteristics socially associated with women is a way to sustain hegemonic masculinity (Baére & Zanello, 2018).

The social and economic changes in Brazil, mainly after abolition, relate to the historical scenario of the effectiveness device. At the time, there was a social ideal characterized by preserving privileges and hierarchies of wealthy, heterosexual white men, the family heads. With the advancement of urbanization, the value given to work and effort became a way to measure men’s masculinity, making sexual performance and productivity at work two important criteria for the idealization of “masculine personality,” reinforcing the hegemony and male domination in society (Zanello, 2018).

An indication of the effect of socialization and the culture in which participants are inserted, which can lead to the relentless pursuit of positions of power and professional success, with the constant need to prove masculinity in the work environment, bringing stress, exhaustion, and difficulty in seeking a healthy balance between work and personal life, can be seen in the following statements:

My mom’s husband keeps reminding her that the house is his, that he supports her, and that she must obey him for that reason. (Student 2)

My sister spent her entire pregnancy being beaten because the guy thought he should hit her just because she depended on him. (Student 3)

It is evident that the effectiveness device brings numerous benefits to men while also placing a burden on them, as it reinforces unattainable and limiting expectations. Additionally, it is important to emphasize that not all men fit these standards, such as gay and transgender individuals, and imposing this masculinity can create a violent and hostile environment for these individuals. Other consequences can be cited, such as stress, anxiety, and limitations in expressing emotions. It is crucial to question these expectations to allow a new experience of masculinity that permits men’s expression in an authentic and healthy manner (Queiroz, 2021). This limitation in expressing emotions was observed during the interventions, as the boys verbalized that “they couldn’t cry” because it would be a reason for mockery from their peers.

22.4 Final Considerations

This article aimed to report on gender literacy interventions conducted with adolescents, students in the 7th, 8th, and 9th grades of a full-time school located in the interior of Ceará State. Below is a self-assessment of the proposal based on the following attributes: impact; coverage; potential coverage; replicability; complexity; innovation.

The impact of the proposal is relevant, considering that the school can be a significant space used to inform about the topic and, consequently, to potentially reduce gender inequality levels that permeate various social layers. The consultancy’s utility lies in facilitating access to the theme, which is still socially disapproved. Similarly, the approach used during the intervention is relevant, facilitating learning and bringing students closer to the topic.

The consultancy will have local coverage. Potential coverage relates to the possibility of expanding and reapplying the proposal, which may be feasible, as it is believed that interventions can be conducted with other students, as well as teachers and staff at the school. Additionally, interventions can be conducted in other educational institutions, with updated content and methodologies.

The intervention can be reapplied, as no difficulties were detected in understanding the theme or the subthemes addressed, nor did it require significant physical infrastructure for the meetings. Furthermore, it is possible to consider that there was positive participation from the students, as they always performed the proposed activities and enhanced the discussions when requested.

The intervention can be considered of medium complexity, as it involved simple activities but required facilitator skills, such as theoretical and empirical knowledge on the topic and effective communication skills, among others.

Finally, the use of active and participatory methodologies, as well as discussing situations and reflecting on potentially unequal gender actions, considering the context and experiences of the participants, provided interaction among the students and facilitated dialogue and knowledge exchange, also enabling behavior changes that can perpetuate gender inequalities, stereotypes, and biases.